Copyright © Jim Foley || Email me

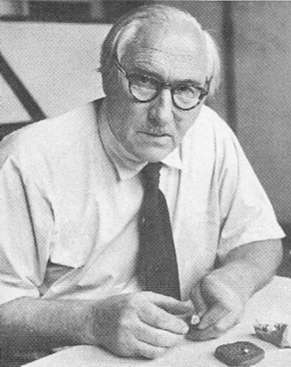

Few people have had more impact on the study of human origins than the

brilliant, passionate, energetic, eccentric and occasionally erratic Louis

Leakey.

Few people have had more impact on the study of human origins than the

brilliant, passionate, energetic, eccentric and occasionally erratic Louis

Leakey.

Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey was born on August 7, 1903 at Kabete Mission, nine miles from Nairobi, Kenya. His parents, Harry and Mary Leakey, were English missionaries to the Kikuyu tribe, and despite brief stays in England during his childhood, Louis grew up more African than English. He played with Africans, learned to hunt, spoke Kikuyu as fluently as English, and was initiated as a member of the Kikuyu tribe. At 13, after discovering stone tools, he was seized with a passion for prehistory and decided that he would learn about the people who made them. In 1922 he started studies at Cambridge, but a rugby accident the following year left him unable to study, and he left to help manage a paleontological expedition to Africa. He returned in 1925 to resume his studies, and graduated brilliantly in anthropology and archaeology in 1926.

Over the next few years, he conducted a number of excavations in East Africa. He was clearly a rising star, and in 1930 was awarded a Ph.D. for his work. In 1932, he discovered fossils at Kanam and Kanjera and claimed that they were the oldest true ancestors of modern humans. On his return to England, these were widely praised as important finds, and Louis' star rose even higher. In response to some doubts, he invited the geologist Percy Boswell to visit the sites during his next expedition (1934-1935) to Africa. Unfortunately, once Boswell arrived, a combination of inadequate documentation and bad luck meant that Leakey could not reliably identify either site. Back in England, Boswell's report seriously damaged Leakey's scientific reputation.

In 1928 Louis had married Frida Avern, an Englishwoman he had met in Africa. While in England in 1933, he met Mary Nicol, a scientific illustrator, and soon started an affair with her despite the fact that he had one young child and a pregnant wife. Mary joined him for his next expedition to Africa, and returned home to live with him in 1935. In 1936, his wife Frida filed for divorce, and Louis and Mary married late that year. The scandals over his personal life and the Kanam and Kanjera fiascos effectively destroyed Louis' promising academic career at Cambridge. Without a steady job, he got a small income from speaking and writing, and in 1937 he returned to Africa to do a massive ethnological study of the Kikuyu tribe.

During the 2nd World War Louis performed intelligence work, but in between his wartime responsibilities he and Mary continued to do archaeological work. In 1941 he was made an honorary curator of the Coryndon Museum (later the Kenya National Museum), and in 1945 he accepted a poorly paid position as curator of the museum so that he could continue his paleontological and archaeological work in Kenya. In 1947, Louis organized the first Pan-African Congress of Prehistory, a successful event which helped restore his reputation and introduced many scientists to the large amount of important work that the Leakeys had accomplished since the Kanam/Kanjera debacle.

He and Mary continued to excavate at many sites during the 1950s, especially Olduvai Gorge in Tanganyika (now Tanzania). Although the discovery of an important Miocene ape fossil in 1948 had given them some attention and led to more funding, money constraints always limited the amount of work they could do. Nevertheless, they continued to make significant discoveries.

In 1959, Mary found their first significant hominid fossil, a robust skull with huge teeth. It was found in deposits that also contained stone tools and Louis, typically, inflated its importance by claiming it was a human ancestor and calling it Zinjanthropus boisei. To everyone else, it seemed markedly unhuman, and most similar to robust australopithecines. Even so, it was a major find that gave them tremendous publicity. The National Geographic magazine printed the first of many articles about the Leakeys and their finds, and gave a large amount of funding which allowed the Leakeys to greatly increase the scope of their excavations at Olduvai. Within a few years they had found many more hominid fossils, including some that were far more plausible human ancestors and toolmakers than Zinj. In 1964, Louis, along with Phillip Tobias and John Napier, named the new species Homo habilis. Although originally controversial, habilis would eventually be widely accepted as a species.

Through the 1950s, Louis and Mary's marriage suffered, mostly from Louis' philandering, but they stayed together, mostly because of their children. In the 1960s, Mary continued to concentrate on Olduvai Gorge, while Louis flitted between many other projects. Most notably, he was responsible for initiating Jane Goodall's decades-long field study of chimpanzees in the wild, and the similar projects of Dian Fossey (for gorillas) and Birute Galdikas (for orang-utans). He was also involved with a primate research center, excavations in Ethiopia, and a search for ancient humans at Calico Hills in California (this last was considered almost a crackpot idea by most scientists), among others. In addition he was doing a lot of travelling, speaking, and fund-raising, much of it in America where he was tremendously popular. On top of everything, his health was rapidly failing, and he was plagued with serious medical problems. He collapsed and died in England in October 1972, aged 69.

A few days before his death, his son Richard had shown him the just-discovered fossil skull ER 1470, which seemed to support Louis' long-held contention that the genus Homo had a long history and had not descended from australopithecines. It also led to a reconciliation between Louis and Richard, who had been clashing personally and professionally for some years. Louis' last few years had been very difficult, but these developments must, at least, have brightened his final days.

Morell V. (1995): Ancestral passions: the Leakey family and the quest for humankind's beginnings. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Louis Leakey (1937): White African. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

Discovering the Secrets of Humankind's Past, by Ted Weiman

Louis Seymour Bazett Leakey (1903-1972)

This page is part of the Fossil Hominids FAQ at the talk.origins Archive.

Home Page |

Species |

Fossils |

Creationism |

Reading |

References

Illustrations |

What's New |

Feedback |

Search |

Links |

Fiction

http://www.talkorigins.org/faqs/homs/lleakey.html, 04/24/98

Copyright © Jim Foley

|| Email me